Release date: 2018-01-22

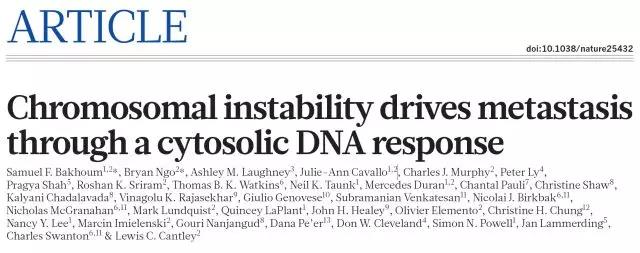

How cancer metastasis has always been one of the central mysteries of cancer biology. The results of the study published by Nature on January 17 seem to partially solve this mystery. The authors track the complex chain of events caused by chromosomal instability (this is a broad feature of cancer cells in which DNA is erroneously replicated whenever these cells divide, resulting in unequal daughter cells of DNA cells). Using breast and lung cancer models, the researchers found that chromosomal instability caused changes in cells that drive metastasis.

"Research has shown that chromosomal instability can lead to the omission of DNA in the nucleus of cancer cells, leading to chronic inflammatory reactions in the cells, which essentially prevent this reaction from spreading to distant organs." Author, Wellcome Nair Medical Holman, Ph.D., and Dr. Samuel Bakum, Senior Resident of Radiation Oncology at the Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

This discovery is mainly the progress of basic science, but it should also have long-term significance for the development of cancer drugs. Senior author Dr. Lewis Cantley, director of Meyer at Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and Professor of Cancer Biology at Weill Cornell said: "Transfer leads to 90% of cancer deaths, and this work opens up new possibilities for therapeutic targeted therapy. Previous Research has linked chromosomal instability to metastasis, although the reasons for this connection are unclear."

Dr. Bakhoum said: "Our initial hypothesis is that chromosomal instability produces many genetically distinct tumor cells, and the Darwin selection process promotes the survival of cells that can diffuse and form distant tumors."

Chromosomal instability is the driving force for tumor metastasis

When he injected chromosomal unstable tumor cells into mice, they were found to be more likely to spread and form new tumors than tumor cells whose chromosomal instability was inhibited. Even though the genes of the two sets of tumor cells are the same and the number of chromosomes is the same, it indicates that chromosomal instability itself is a driving factor for metastasis.

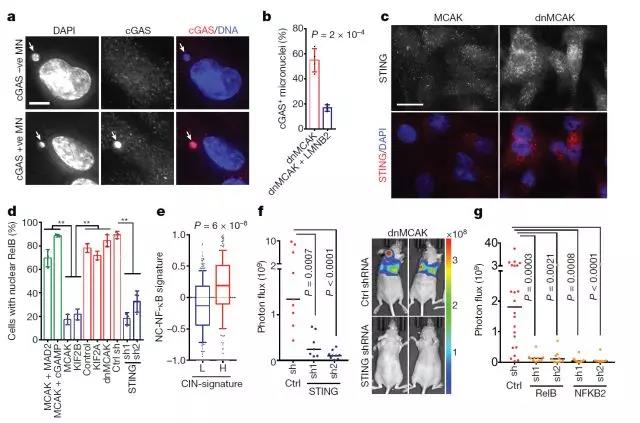

The researchers examined gene activity in these two groups of tumor cells. They found that those with highly unstable chromosomes had abnormally elevated activity due to more than 1,500 genes, especially those involved in inflammation and the immune system's response to viral infections. Dr. Bakhoum said: "These cancer cells are cultured in culture dishes and there are no immune cells. We are very surprised and wonder what might be causing this inflammatory response."

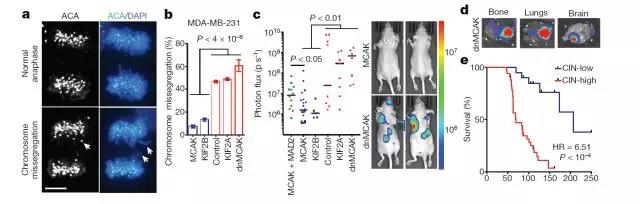

Recent research in other laboratories provides some clues that chromosomes in unstable tumor cells sometimes leak out of their normally present nuclei. These mislocated chromosomes encapsulate themselves in the liquid or cytoplasm of the major part of the cell outside the nucleus to form a "micronucleus." However, the micronucleus eventually ruptures, releasing the naked DNA into the cytosol.

Cells interpret DNA in the cytosol as a marker of infection, and when it first attacks a cell, it typically releases its DNA in the cytoplasm.

Human cells have evolved to combat this type of viral infection by sensing naked cytoplasmic DNA using a molecular machine called the cGAS-STING pathway. Once activated, this pathway triggers an inflammatory antiviral regimen.

DNA transfer-induced cancer metastasis

Dr. Bakhoum and colleagues examined their chromosomally unstable tumor cells and found that they did have large amounts of cytosolic DNA and showed evidence of chronic activation of the antiviral cGAS-STING protein. Decreasing cGAS-STING levels reduces the inflammatory response and prevents the ability of invasive tumor cells to metastasize when injected into mice.

In ordinary cells, an antiviral response stimulated by nuclear DNA leakage quickly leads to cell death. However, the researchers found that tumor cells have successfully suppressed the lethal elements of the cGAS-STING response. At the same time, they use other parts of the reaction to get themselves out of the tumor and move around in the body.

Dr. Bakhoum said: "They started to behave as if they were some kind of immune cells, and these immune cells are usually activated by infection. In response, they quickly move to the infected or injured area, so that the cancer cells will participate in some kind of fatal Immune imitation."

Researchers have estimated that about half of human metastases occur in this way based on recent studies of metastatic tumor characteristics. They are currently investigating strategies to stop this process. Since tumor cells themselves are prone to this, positioning chromosomal instability itself may not be feasible, Dr. Bakhou said. However, he pointed out that "chromosome-unstable tumor cells and their cytoplasmic DNA are basically filled with their own toxins." In principle, the ability to revoke their ability to inhibit normal and lethal antiviral responses to cytoplasmic DNA will rapidly kill these invasive cancer cells with minimal impact on other cells.

Dr. Bakhoum said: "One of our next steps is to better understand how these cells change the normal response and how to restore normal response."

references:

Samuel F. Bakhoum, Bryan Ngo, Ashley M. Laughney, Julie-Ann Cavallo, Charles J. Murphy, Peter Ly. Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response.

Source: Translational Medicine Network

Voice Evacuation System,Fire Broadcasting Control System,Voice Evacuation Control Panel,Fire Emergency Broadcast System

LIAONING YINGKOU TIANCHENG FIRE PROTECTION EQUIPMENT CO.,LTD , https://www.tcfiretech.com